Butyrate: The Short-Chain Fatty Acid That Holds the Key to Your Gut and Overall Health

If your digestive system were a bustling city, butyrate would be the foundation holding the entire infrastructure together. This powerful short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) plays a vital role in gut barrier integrity, inflammation control, brain health, immune balance, and even metabolic function.

Unfortunately, most people aren’t producing enough of it—leading to a cascade of health issues. The good news? Butyrate production is something you can influence.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore:

-

What butyrate is and how it’s made in the gut

-

Why it’s crucial for your health

-

The signs and consequences of low butyrate

-

How to test your butyrate levels (Gut Zoomer test)

-

The most effective ways to increase it naturally and clinically

What is Butyrate?

Butyrate (also called butyric acid) is one of the three main SCFAs produced by your gut microbiota when they ferment dietary fiber. The other two are acetate and propionate, but butyrate stands out for its uniquely important roles:

-

Serving as the primary fuel source for your colon cells (colonocytes)

-

Strengthening the intestinal barrier to prevent leaky gut

-

Regulating inflammation and immune activity

-

Supporting brain health and mood regulation via the gut-brain axis

Butyrate is produced in small amounts naturally, but its impact is massive—like a master switch for gut and whole-body wellness.

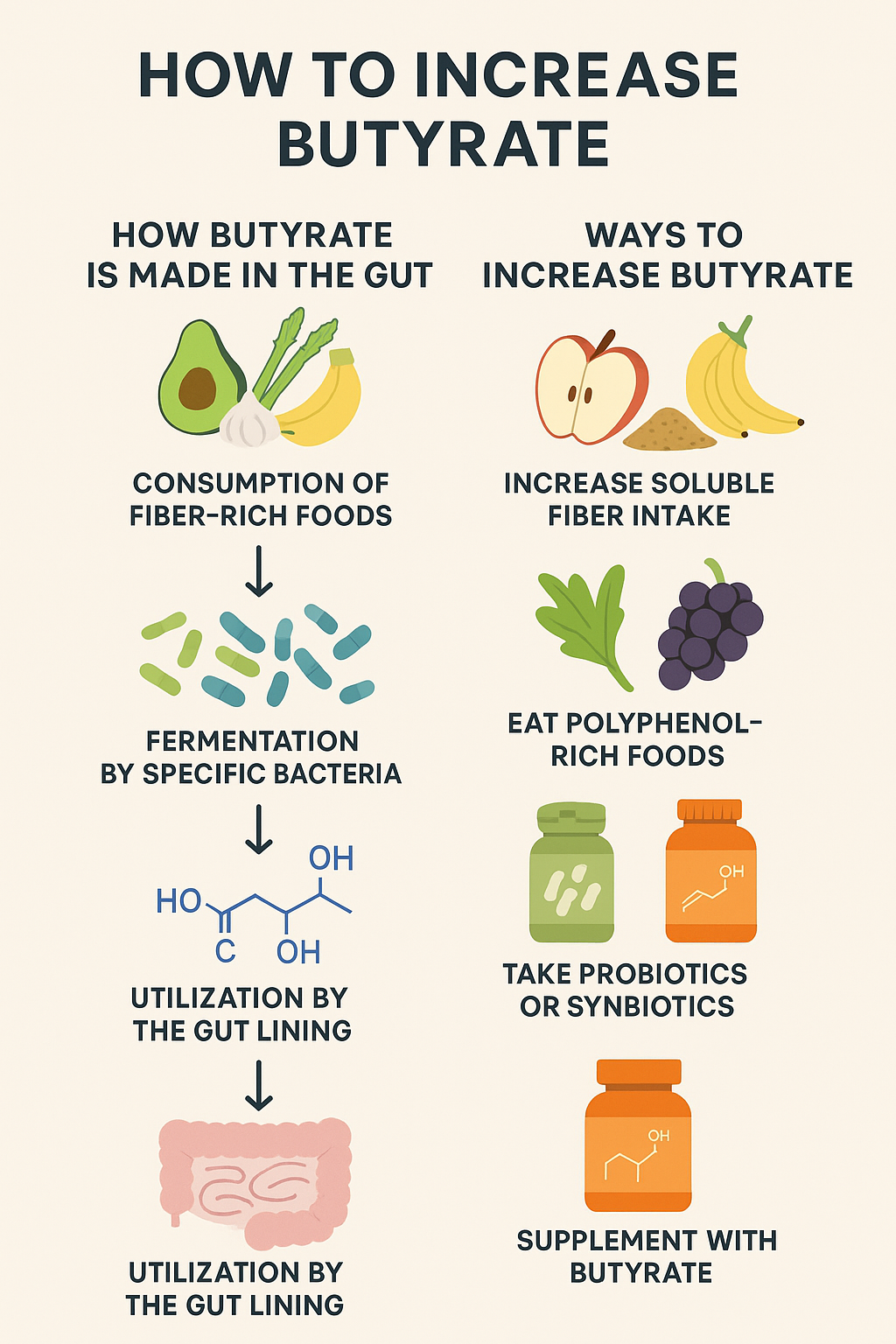

How Butyrate is Made in the Gut

The process starts when you eat fiber-rich foods—especially certain prebiotic fibers that your body can’t digest. Instead, they travel intact to the colon, where your beneficial bacteria ferment them, producing SCFAs.

Key steps in the process:

-

Consumption of fermentable fibers and resistant starches

-

These include foods like green bananas, cooked-and-cooled potatoes, oats, garlic, onions, leeks, asparagus, and many vegetables.

-

-

Fermentation by specific bacteria

-

Certain gut microbes specialize in producing butyrate, including:

-

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii

-

Roseburia hominis

-

Eubacterium rectale

-

-

-

Production of SCFAs

-

Bacteria ferment fibers into SCFAs, and butyrate is absorbed by colonocytes or enters circulation to influence distant organs.

-

-

Utilization by the gut lining

-

About 90% of butyrate is used locally by the colon to keep the lining healthy and sealed.

-

Why Butyrate is So Important

1. Maintains Gut Barrier Integrity

Butyrate fuels colonocytes, enabling them to produce tight junction proteins that prevent unwanted substances (toxins, undigested food particles, pathogens) from leaking into your bloodstream.

2. Reduces Gut Inflammation

It inhibits NF-κB, a major pro-inflammatory pathway, and stimulates regulatory T-cells, which keep the immune system balanced.

3. Supports Brain and Mental Health

Through the gut-brain axis, butyrate acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, influencing gene expression linked to neuroplasticity, mood regulation, and cognitive function.

4. Regulates Immune Function

Butyrate helps immune cells differentiate properly, reducing autoimmunity risk and improving tolerance to harmless foods and microbes.

5. Aids in Metabolic Health

It improves insulin sensitivity, supports weight management, and may help reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Signs You May Have Low Butyrate Levels

While low butyrate doesn’t have a single symptom, it often accompanies gut dysbiosis and may manifest as:

-

Frequent bloating or gas

-

Chronic constipation or diarrhea

-

Food sensitivities

-

Recurrent infections or poor immune resilience

-

Brain fog or low mood

-

Inflammatory conditions (IBD, IBS, autoimmune disorders)

How We Test for Butyrate Levels

At our clinic, we measure butyrate levels as part of the Gut Zoomer test.

The Gut Zoomer provides:

-

Quantitative SCFA levels (including butyrate, acetate, propionate)

-

Microbial diversity score

-

Identification of specific butyrate-producing bacteria

-

Insights into dysbiosis patterns and intestinal inflammation

This testing allows us to create a targeted gut restoration plan instead of guessing. If your butyrate is low, we know exactly which foods, supplements, and lifestyle strategies will help restore balance.

Causes of Low Butyrate

Low butyrate often results from:

-

Low-fiber diet (especially low in resistant starch)

-

Antibiotic use (reducing butyrate-producing bacteria)

-

Chronic stress (alters gut microbiome composition)

-

Overuse of processed foods and sugars (promotes harmful bacteria)

-

Intestinal inflammation (harms colonocytes and SCFA absorption)

-

Low microbial diversity (fewer species capable of producing butyrate)

How to Increase Butyrate Naturally

1. Eat More Resistant Starch

Resistant starch resists digestion in the small intestine and ferments in the colon, feeding butyrate-producing bacteria.

Best sources:

-

Cooked-and-cooled potatoes

-

Green bananas or plantains

-

Cooked-and-cooled rice

-

Legumes (lentils, chickpeas, beans)

-

Oats

2. Increase Soluble Fiber Intake

Soluble fiber feeds beneficial bacteria and boosts SCFA production.

Sources include:

-

Psyllium husk

-

Apples, pears

-

Brussels sprouts

-

Flaxseeds and chia seeds

3. Eat Polyphenol-Rich Foods

Polyphenols (found in berries, green tea, and dark chocolate) enhance the growth of butyrate-producing bacteria.

4. Probiotics and Synbiotics

While probiotics alone may not directly produce butyrate, certain strains (Clostridium butyricum, Lactobacillus plantarum) encourage the growth of butyrate producers. Combining them with prebiotics (synbiotics) maximizes benefits.

5. Supplement with Butyrate

Sodium butyrate or tributyrin supplements can provide direct butyrate to the colon. These are particularly useful when the gut is inflamed or microbiome diversity is low.

6. Reduce Gut Irritants

Limit artificial sweeteners, excess alcohol, processed foods, and unnecessary antibiotics.

7. Support Overall Microbiome Diversity

Eat a wide variety of plant-based foods, fermented foods, and rotate fiber sources.

Advanced Clinical Strategies for Low Butyrate

In some cases, dietary changes alone aren’t enough—especially if there’s significant dysbiosis, leaky gut, or inflammation. In these situations, we may recommend:

-

Targeted prebiotics (partially hydrolyzed guar gum, arabinogalactan)

-

Spore-based probiotics (e.g., Bacillus coagulans) to enhance SCFA production

-

Anti-inflammatory nutrients like Curcumin Complex and Omega 1300 to heal the gut lining

-

Immunoglobulin G supplements like Immuno-30 to reduce gut inflammation

Fixing Low Butyrate: Our Step-by-Step Approach

When your Gut Zoomer shows low butyrate, here’s our typical protocol:

-

Identify the cause (dietary, microbial imbalance, inflammation)

-

Remove gut disruptors (processed food, alcohol, artificial additives)

-

Repopulate with beneficial bacteria via probiotics and fiber-rich foods

-

Provide direct butyrate support with sodium butyrate or tributyrin

-

Heal the gut lining with nutrients and peptides

-

Retest in 3–6 months to track progress

The Bottom Line

Butyrate is more than just a gut health marker—it’s a central player in your digestive, immune, metabolic, and even mental well-being. Without enough of it, your gut barrier weakens, inflammation rises, and your resilience to disease declines.

The Gut Zoomer test gives us a clear picture of your butyrate production so we can create a targeted, effective plan to restore it.

If you’re experiencing digestive issues, inflammation, or unexplained fatigue, it may be time to check your butyrate levels and take steps to optimize your gut health.

Take the first step toward a healthier gut—schedule your Gut Zoomer test with us today and find out if your butyrate levels are where they should be.

References

-

Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(1):29-41.

-

Canani RB, et al. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(12):1519–1528.

-

Kelly CJ, et al. Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):662-671.

-

Dalile B, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(8):461–478.